A Quiet Success with Broader Implications

As the UK approaches the implementation of its national Deposit Return Scheme (DRS), much attention is turning to European examples for insight. Among them, Sweden stands out, not through flashiness or groundbreaking tech, but through quiet consistency. With one of the longest-running DRS programs in the world, Sweden has established a national habit of container returns that many countries admire. However, as the UK builds its system, the lessons from Sweden are not only about what works but also about what may no longer be sufficient.

A System Rooted in Simplicity

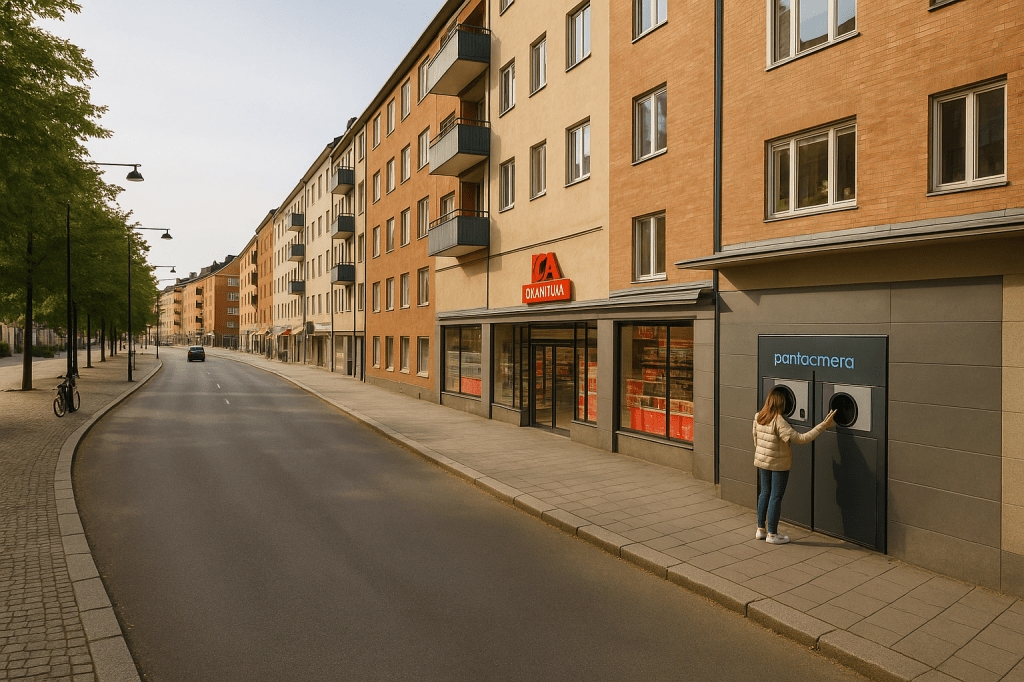

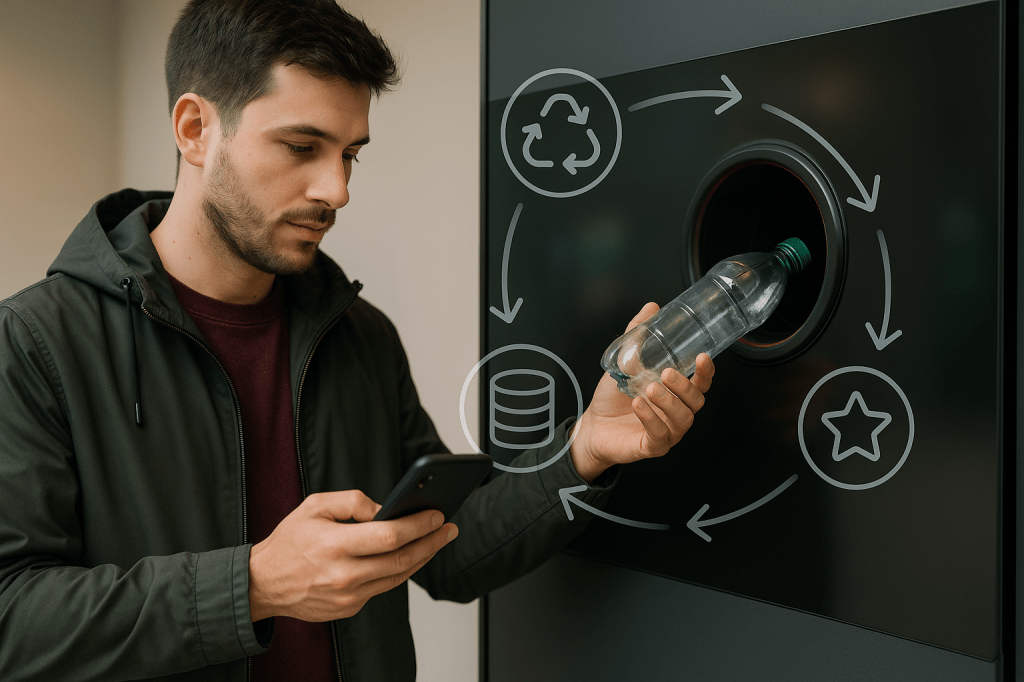

Sweden’s DRS has existed since the 1980s, built on a simple but effective idea: make container returns easy and familiar. The system integrates into daily life; people return beverage containers at grocery stores, receive their deposits back, and move on. Supermarkets host the machines, producers support logistics, and consumers understand the process without needing to overthink it. The result is one of Europe’s highest return rates and a public that sees the scheme not as a policy requirement but as a shared civic habit.

When Familiarity Limits Flexibility

But while Sweden’s approach excels in consistency, it also shows signs of age. The infrastructure, though effective, was designed in a pre-digital era. There are limited opportunities for real-time engagement, behavioral insights, or cross-sector collaboration. The model is transactional and primarily focused on physical collection. It fulfills its original purpose, but the environmental, technological, and policy context has evolved considerably since its inception.

Today’s sustainability challenges require more than container refunds; they require interconnected thinking. Circularity, traceability, and behavioral participation are becoming central to public expectations. In this regard, Sweden’s model begins to feel like a well-kept classic car in a world moving toward smart mobility.

The UK’s Distinct Window of Opportunity

The UK stands at a very different point in time than Sweden did when its scheme began. It has access to contemporary digital tools, emerging circular economy frameworks, and a public increasingly engaged in environmental accountability. This creates a rare opportunity to design a system that maintains the clarity and usability seen in Sweden while allowing for layers of future adaptation.

This doesn’t mean the UK needs to build something flashy or over-engineered. However, it does mean the system should leave space for innovation, external collaboration, public engagement beyond refunds, and more nuanced responses to data, geography, and behavior.

Why Structural Design Now Matters Later

A DRS should not be viewed solely as an operational tool; it is also a civic interface. If designed thoughtfully, it can become a gateway into wider forms of environmental participation. This requires a flexible backbone, one that is capable of linking with other public platforms or policy channels as needed. It’s not about locking in complex features now but about ensuring the system doesn’t lock them out in the future.

Sweden’s reliance on grocery retail, for instance, has worked well within its compact geography and urban density. But the UK, with its broader regional variations and devolved governments, may benefit from more distributed return models. Such models don’t rely solely on supermarkets but allow for community returns, mobile collection hubs, or even collaborative approaches involving local authorities and retailers alike.

Looking Beyond Refunds

One of the most critical opportunities for the UK lies in recognizing that deposits and returns are just one part of the circular equation. Sweden’s system excels in single-use collection, but it has yet to adopt container reuse or data-driven lifecycle visibility fully. These are areas where UK policy and innovation may choose to go further, not by reinventing the scheme outright but by creating a framework open to brilliant adaptation and stakeholder alignment over time.

There is already growing interest in how DRS data can align with other sustainability metrics, as well as how local incentive schemes can encourage not only compliance but also environmental enthusiasm. These ideas remain conceptual today, but the direction is clear: countries that build with flexibility will be the first to adapt when expectations change again.

Following Sweden’s Example, But Not Its Limits

Sweden has delivered one of the most effective return systems in the world thanks to its coherence, simplicity, and centralized coordination. These are qualities the UK should take to heart. But the UK must also recognize that it is launching in a far more complex and digitally integrated environment. What worked brilliantly in the past may not meet the full range of needs and opportunities available today.

This is not a matter of rejecting Sweden’s model. It’s about respecting it while realizing that the next wave of circular infrastructure may require more than it was ever meant to do.

A Time to Lead, Not Just Follow

The UK’s DRS will be one of the most visible environmental systems in the country. It will shape how citizens participate in recycling, how brands demonstrate responsibility, and how regions respond to climate goals. Sweden’s DRS teaches us that trust, clarity, and public cooperation can build a lasting system. But it also reminds us that systems must evolve if they are to stay relevant.

The UK has a chance not only to learn from Sweden but to build something that anticipates the future. A return scheme that doesn’t just manage containers but contributes meaningfully to the connected, adaptive, and circular society we need.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

“Stay informed. Subscribe for more insights on sustainable tech and circular economy solutions.”

Leave a comment